Scribe: The composer as palaeographer

By Mark Dyer

In a recent blog post, I introduced the first stages of Scribe, a creative project in which I trained a neural network (a form of machine learning) on pages of the medieval ‘Old Hall’ music manuscript.

Presented with the machine’s outputs – thousands of glitchy images with increasing likeness to the manuscript – I began working under the pretence the network was actually a medieval scribe, copying out ‘new’ compositions, each image a fragment of a fabricated facsimile manuscript .

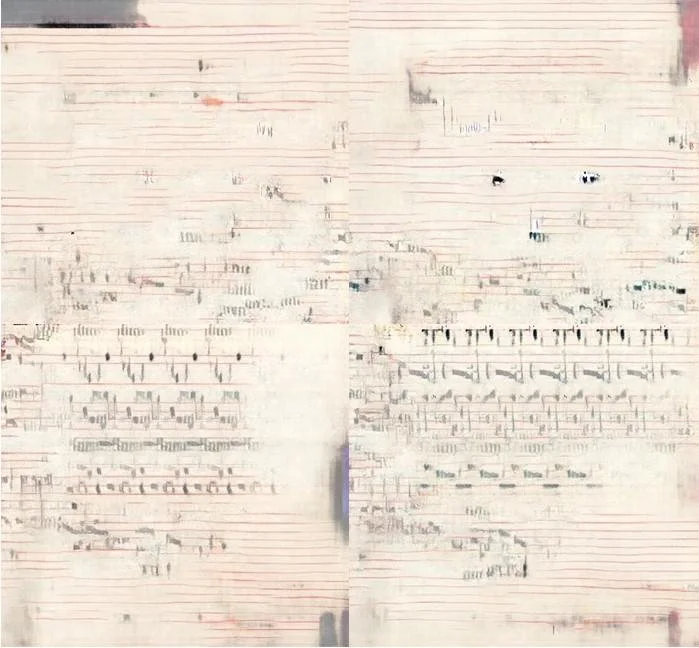

I then acted as palaeographer – one who assembles and deciphers ancient texts – and started pairing and arranging images into the pages of this manuscript. As palaeographer, I needed to make sense of these strange images, following semi-regulated rules. Below is an example ‘page,’ compiled from four images - clockwise from top left, these are epochs 4010(1), 4005(1), 4005(0) and 4010(2).

‘Page’ of Scribe score, compiled of four machine-learning generated images, epochs 4010(1), 4005(1), 4005(0) and 4010(2)

Roughly, I aligned the red stave lines, left to right. The marks on the upper margins perhaps hint at the manuscript binding beneath, whilst the C-clef in the top-left corner of image 4010(2) (indicated in the second example below) suggests the left-hand side of the page.

Before transcribing the notation, I had to interpret my invented page. I identified three musical voices. The cantus is written faintly over one system with its own text at the bottom of 4010(1) and 4005(1):

The countertenor and tenor are paired across two systems of repetitive figures in 4010(2) and 4005(0), sharing a separate text.

I then transcribed individual voices, a balancing act between rigorous transcription following Willi Apel’s The Notation of Polyphonic Music 900-1600 (2010) and editorial license, jigsawing voice durations and harmonies together.

Let’s look at the first bars of the example page. Given the clef in the countertenor, I added clefs to the other voices to create an appropriate opening harmony. Next, I calculated the mensuration (equivalent to a modern time signature) of each voice: a back-and-forth process navigating the ambiguities of mensural notation and the low-resolution images.

For instance, interpreting a skewed notehead in the countertenor as a square breve would suggest one mensuration and ensuing harmony with the tenor, and as a diamond semibreve a separate mensuration. Each reading would open and close myriad possibilities. I see this iterative patching as a playful dialogue with the machine-generated notation, an affective agent in the creative process of Scribe.

In my next post, we’ll look at bringing this notation to life with EXAUDI vocal ensemble.

Videos of EXAUDI’s performances of the Marian Antiphons and Settings of the Mass by Marcel le Gan, edited by Mark Dyer are now online. Visit our page for Scribe to view them.